Design of System Response

Options to handle errors, learn from mistakes, and build resiliency

As we learned last week, human engineering is concerned with how individuals interact with machines. But this isn’t the end of the matter. To understand systems and make them capable, resilient, and efficient we must also appreciate the limits of these human-machine interactions. These limits are particularly important in tasks where human judgment, discernment, evaluation and decision making are concerned.

How can an individual discriminate between something good and bad? Desirable and undesirable? Normal and abnormal? Human-system interactions not only affect the ability to make these distinctions, but they may also define these distinctions in the first place!

A Tale of Two Processes

Consider two different processes at a large pizza franchise, let’s call it Pizza Hat. Around the US, Pizza Hat has several facilities that produce fresh dough. The dough is shipped to the franchise locations, where it is used to make made-to-order pizzas.

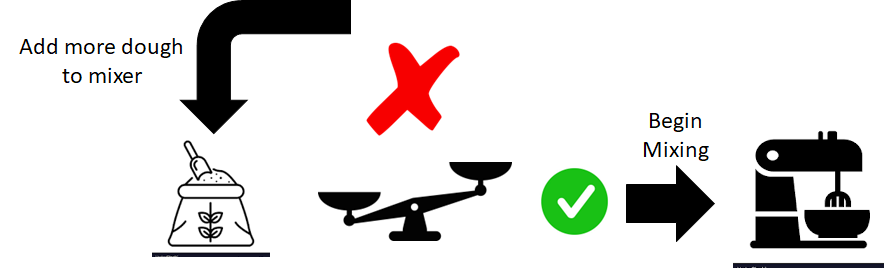

The first part of dough making process involves mixing a large batch of flour and water in a mixer. The process is a small feedback system. A set amount of flour is dumped into the mixer, the mixer is weighed, and if more flour is required, more is added. The process is then repeated for adding the water.

After the dough is produced in the mixer, it goes down a conveyor and through a metal detector. This protects the customer and ensures that no flakes of metal have come off of the machines in the mixing process.

The way the metal detector evaluates the dough is very different from the mixer. The metal detector evaluates each ball of dough as pass/fail. In this part of the process, the system is not interested in measuring the amount of metal in each ball but detecting whether any metal is in the dough ball.

The mixing process measures amounts and can adjust accordingly. The mixer process can recover from deviations from the recipe in a way that isn’t possible with the metal detector. All of this is dictated by the design of the system.

The Response Determines Everything

Systems play an important role in determining what happens next. The response. The dough with metal in them are pulled from the production line and trashed. If the dough recipe is underweight, more dough and water can be added to get the recipe just right. The entire batch of dough is not scrapped just because it is underweight. The way the system is designed will determine what options are available to address the problem.

This is a critical insight: the design of the system determines not just whether errors are caught, but what can be done about them when they occur. A well-designed system creates options for correction and recovery. A poorly designed system may detect problems but leave no good options for fixing them. You’ve probably heard that the medium is the message. Well, I don’t have something as pithy as that for system responses, but the same general idea holds true. You get the idea, right?

Speaking broadly, we can categorize the responses into four categories, arranged from least to most effective:

Method 1: Self-Monitoring

The first way is self-monitoring. Here, the individual is solely responsible to identify issues and errors. Self-monitoring requires the individual to monitor their own performance, identify outputs of the system, evaluate if those outputs should be considered worthy of intervention, and respond appropriately based on their diagnosis.

As an example, a nurse might need to draw blood from a patient. She will need to evaluate the condition of the syringe, locate the vein, sterilize the skin, insert the needle, begin the blood draw, stop the blood draw, and bandage the wound. In each of these circumstances she will need to evaluate whether the work was done satisfactorily or if it requires rework. If you’ve ever had a nurse miss your vein, you know how cumbersome this can be.

It’s a lot to ask a single person to do and there are likely better, more reliable ways of building systemic capability and resiliency.

The Limitations of Self-Monitoring

Self-monitoring places the entire burden on the individual. They must:

Maintain constant vigilance

Remember all the standards and criteria

Notice when something goes wrong

Correctly diagnose the problem

Know how to fix it

Actually implement the fix

This is exhausting and error-prone. People get tired, distracted, rushed, and complacent. They forget things. They miss signs. They make incorrect assumptions. Relying solely on self-monitoring is the weakest form of error detection and correction.

Yet this is exactly how many personal productivity systems work. You’re supposed to remember to check your task list, remember to follow your morning routine, remember to track your habits, remember to review your goals. The system provides no support. It rests solely on you.

Method 2: Monitoring by Others

Of course, the monitoring and detection of issues in a system do not have to be monitored by the individual doing the work. Others can have the task of monitoring work as well. There are various forms of detection and response by others, from independent monitoring, concurrent monitoring and verification, and downstream inspection.

Independent Monitoring

In this approach, someone else periodically checks the work. A manager reviews reports. A quality inspector examines products. An editor reviews written content. This is better than self-monitoring because it provides a fresh perspective and removes some burden from the primary worker.

However, independent monitoring has its own limitations. It’s resource-intensive, i.e. you need additional people. It’s often delayed, i.e. problems aren’t caught until the inspection happens. And it can create a false sense of security, where workers become less careful because they know someone else will catch their mistakes.

Concurrent Monitoring

A more sophisticated approach is concurrent monitoring, where verification happens alongside the work. In software development, this is pair programming. In medicine, it’s having a second nurse verify medication doses. In aviation, it’s the pilot and co-pilot cross-checking each other’s actions.

Concurrent monitoring is more effective than periodic inspection because it catches errors immediately, when they’re easiest to correct. But it still requires significant resources and relies on human vigilance.

Downstream Inspection

Many processes use inspection checkpoints where work must pass through verification before proceeding to the next stage. Manufacturing quality control, software testing, and financial audits all use this approach.

Downstream inspection is better than nothing, but it has a fundamental weakness: it catches errors after they’ve already occurred and potentially propagated. You’ve already spent time and resources creating defective work. Now you have to spend more time and resources identifying, analyzing, and correcting or discarding it.

Method 3: Environmental Error Cueing

Error cueing is the third way to respond. In this response method, the system or environment detects an issue, a non-conformance, or an error and cues us, as individuals of the error. In the pizza dough example, the metal detector let out a loud siren when metal was detected.

There are various levels of error cueing with various degrees of diagnosis and signaling to the individual. In this method of response, the human operator is still the ultimate decider and actor. Supported by the environmental cue, the human actor can determine if the cue was correct or not, and what how to respond.

Blocking: The Power of Prevention

The most unambiguous way the environment can cue us that we have made an error is to prevent or obstruct our progress onward, a strategy known as blocking. Consider a few examples:

Keys and locks, sign on screens and passcodes — Prevent proceeding on your journey until you have provided an adequate level of permission. In the case of doors, having a key is considered adequate permission. In the virtual world, sign on screens and passcodes (and account settings) provide the information necessary to proceed.

Deadman’s bar — Devices like lawnmowers require the user to hold a “deadman’s bar” in order to keep the motor running. Failure to do this results in the engine stopping. This is actually a fantastic safety feature to prevent the operator from putting their body in harm’s way.

Blocking prevents you from making certain errors in the first place. You can’t enter a room without the key. You can’t run a lawnmower without holding the safety bar. The system physically prevents the wrong action.

Forcing Functions: Taking Blocking Further

Blocking is already a great response to system errors, and can be augmented still, with the use of forcing functions. Forcing functions are things that prevent “the behavior from continuing until the problem has been corrected” (Lewis & Norman, 1986, p 420.)

Ground Fault Circuit Interrupter (GFCI) switches provide a superb example. Not only will the GFCI shut off electricity when a ground fault occurs, it will also prevent future use of the circuit until the problem is resolved, and the outlet is reset (usually by pressing a button).

The benefits of forcing functions over blocking are clear and straightforward. The existence of appropriate forcing functions all but guarantees error detection. When using forcing functions, it’s important to keep basic design principles in mind: The earlier a forcing function happens after the propagation of an error the better it is to signal what the error is. Similarly, forcing functions should have clear indicators of success and failure.

Why Error Cueing Works

Error cueing is more effective than human monitoring for several reasons:

Consistency: The system doesn’t get tired, distracted, or complacent

Immediacy: Errors are flagged the moment they occur

Reduced burden: The individual doesn’t have to maintain constant vigilance

Clear feedback: There’s no ambiguity about whether something is wrong

However, error cueing still requires human response. The system can tell you there’s a problem, but you still have to figure out what to do about it.

Method 4: Automatic System Responses

So far, all response methods rely on an individual, with varying degrees of responsibility for detecting, diagnosing, and correcting problems. However, the system itself can respond as well. In fact, the error-cueing method just discussed is a less sophisticated form of automatic system response. In addition to cueing the individual of an error, systems have a number of options on how it can respond automatically.

The Range of Automatic Responses

Gagging — Forcing function that prevents users from expressing unrealizable intentions. i.e., locking keyboard to prevent further typing until the terminal is reset.

Warnings — Informs users of potentially dangerous situations. The user is left to decide and the ultimate decision rests with the individual.

Do Nothing — The system does nothing to respond to an error. (Yes, doing nothing is sometimes a valid response, particularly for non-critical variations.)

Self-Correct — The system identifies the error, determines what the desired goal was, and then makes adjustments to reach the desired goal. This is very sophisticated. You might be familiar with spelling corrections on your smartphone. This in itself may have possibilities for errors and may actually create more. It is a best practice for this to be with warnings/indications to alert the user of the automatic change, so that the operator can determine if the correction was correct and identify possible root cause to prevent further issues.

Let’s talk about it — The system provides information and data and the user enters into a “dialog” with the system to detect and fix the errors. This is the way programming debuggers work—initiated by a detailed description of the issue or error code and an iterative user/machine interaction until the problem is resolved.

“Teach me” — The system detects an issue and requests inputs from the user to understand why, and if the user determines this to be correct, the user determines it as such. Natural language processing works this way for unknown words. For error detection this works best after a warning system where the user does nothing or a self-correct that is reversed.

The Power and Peril of Automation

Automatic system responses represent the pinnacle of error handling. When done well, they provide immediate, consistent, appropriate responses to problems without requiring human intervention. The system detects the problem, diagnoses it, and fixes it all before the human even knows something was wrong.

But automation isn’t always the answer. Over-automation can create new problems:

Users become deskilled and unable to handle exceptions

Automated corrections can sometimes be wrong, creating cascading errors

People lose understanding of how the system actually works

When automation fails, recovery is more difficult

The key is to use automatic responses appropriately for well-understood, repetitive problems where the correct response is clear and consistent.

Choosing the Right Response Method

To design systems that are efficient, effective, and resilient, we cannot simply look at the best practices that will decrease the likelihood of error (the human engineering side of things). We must also consider which methods of response are most appropriate, reliable, and effective for the needs of a system.

The choice depends on several factors:

Criticality: How bad is it if this error occurs? Nuclear reactor controls need forcing functions. A typo in an email probably just needs spell-check suggestions.

Frequency: How often does this error occur? Common errors deserve more sophisticated responses. Rare errors might be fine with just monitoring.

Consequences: Can the error be easily undone, or does it create permanent damage? Reversible errors can tolerate lighter responses.

Clarity: Is the correct action always obvious, or does it require judgment? Clear-cut situations can use automation. Ambiguous situations need human input.

Resources: What’s the cost of implementing different response methods? Sometimes the ideal solution isn’t feasible, and you need the best practical option.

The Hierarchy of Effectiveness

While the choice depends on context, there’s a clear hierarchy of effectiveness:

Automatic prevention/correction (Best) — The system prevents errors or fixes them automatically

Forcing functions — The system blocks progress until the problem is resolved

Environmental blocking — The system prevents certain actions from being taken

Error cueing with immediate feedback — The system alerts you right when the error occurs

Concurrent monitoring by others — Someone checks your work as you do it

Downstream inspection — Someone checks your work after completion

Periodic review — Someone eventually looks at the work

Self-monitoring (Worst) — You’re responsible for catching your own errors

Notice that the most effective methods shift responsibility from the individual to the system. The least effective methods place the entire burden on human vigilance and consistency.

Practical Applications

Consider how these response methods apply to common situations:

Email mistakes:

Self-monitoring: Proofread before sending (least effective)

Error cueing: Spell check underlines errors (better)

Forcing function: “You mentioned an attachment but didn’t include one. Send anyway?” (better still)

Automatic: Undo send feature gives you a window to catch mistakes (best)

Financial errors:

Self-monitoring: Remember to track expenses (least effective)

Monitoring by others: Accountant reviews at tax time (better)

Error cueing: Budget app alerts when overspending (better still)

Automatic: Direct deposit and auto-pay prevent missed payments (best)

Health and safety:

Self-monitoring: Remember to wear safety gear (least effective)

Monitoring by others: Supervisor enforces safety rules (better)

Error cueing: Machine beeps if guard is removed (better still)

Forcing function: Machine won’t start without guard in place (best)

Building Resilient Systems

Taken together, considerations of human engineering and these four methods of response provide a foundation for building truly resilient systems. The goal isn’t to eliminate humans from systems—that’s neither possible nor desirable. The goal is to create systems where human strengths are amplified and human weaknesses are compensated for.

A well-designed system:

Uses human engineering to make correct actions intuitive

Implements appropriate error detection for the criticality of the task

Provides clear, immediate feedback when problems occur

Offers reasonable options for correction and recovery

Automates what should be automated and preserves human judgment where it matters

The key insight is this: the method of response is as important as the method of prevention. You can have the best-designed interface in the world, but if the system’s response to errors is poor, the overall system will be poor.

When you’re designing systems, whether it’s a work process, a personal routine, or a complex industrial operation, don’t just think about how to prevent errors. Think about what happens when errors inevitably occur. How will they be detected? How quickly? By whom or what? What options will be available for correction? How much disruption will the error cause?

The answers to these questions determine whether your system is fragile or resilient, whether it requires constant supervision or runs reliably, whether small errors cascade into disasters or are caught and corrected before they matter.

That’s the power of thoughtful response design.

This highlights the need for "systems intelligence" for "system intelligence" to emerge. Interpreting one's experience as part of the system.

beautiful work, thank you...in the context of imagining how one might be integrating agentic AI into human systems, your framework provides thoughtful insights.